I just finished up a new working paper (available here) with my Purdue ag econ colleague Nathan Thompson and Shawna Weimer, a soon-to-be assistant professor of poultry science at the University of Maryland.

Readers may recall my post from a couple months ago on consumer demand for slow-growth chickens. This new paper focuses on producer costs of switching to slow-growth broiler chicken. Here’s the motivation from the paper (references removed for readability):

“While modern broilers only live about six weeks, there are concerns that the bird’s legs are unable to adequately support the larger bodyweights, leading to pain and an inability to exhibit natural behaviors. As a result of such findings, animal advocacy organizations have begun to pressure food retailers to use slower growing breeds, European regulators have encouraged slow growth broilers, national media attention has begun to focus on the issue, and some animal welfare standards and labels have begun to require slower growing broiler breeds. There has been some consumer research on demand for this attribute, but little is known about the added production costs associated with slow growth chickens.”

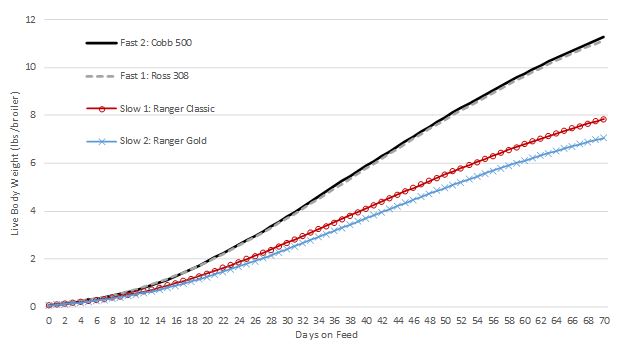

We obtained data from commercial breeding companies on two slow growth broiler breeds (called Ranger Classic and Ranger Gold) and data on two modern fast growing breeds (called Ross 308 and Cobb 500). Here are the growth curves for the four broiler breeds:

The two slow growth breeds are, well, slower growing. The slower-growing breeds take 54 and 59 days, respectively to reach 6 lbs, whereas the faster growing breeds both hit this target weight in about 41 days.

These growth data are combined with data on feed intake, prices, assumptions about stocking density, and more, and we calculate costs and returns under a number of different scenarios. Here are the main results for the most likely scenario where producers choose the number of days to feed broilers so as to maximize net returns and where slow growth broilers have a more generous stocking density than fast growth broilers, as dictated in many animal welfare guidelines.

About 17.45 lbs/ft2/year (or 73%) more chicken on a dressed weight basis is provided by the two fast vs. two slow growth productions systems, on average. Thus, substantially more barn space, or square footage, would be required to produce the same volume of chicken from slow as compared to fast growth breeds. Costs of production average $0.54/lb for the two slow growth breeds and average $0.47/lb for the two fast growth breeds, implying costs are 14% higher per pound for the slower growth breeds. Fast growth breeds are substantially more profitable - generating returns about twice as high per square foot than the slower growth breeds. We calculate that the slower growth broilers would need to obtain wholesale price premiums of $0.285/lb and $0.363/lb to achieve the same profitability as the best performing fast growth breed.

We also use these estimates to calculate potential market impacts that would occur if the entire industry transitioned from fast to slow growth broiler breeds. Under the most likely scenario, we calculate that converting to slow growth breeds would increase retail chicken prices by 1.17% and reduce the amount of retail chicken sold by 0.91%, resulting in losses in producer profits of $3.5 billion/year. We also calculate that consumers would be worse off by $630 million/year, assuming their demand for chicken doesn’t change in response to the switch from slow to fast growth. Increases in consumer willingness-to-pay of 8.5% would be needed to offset the adverse effect on producer profits.