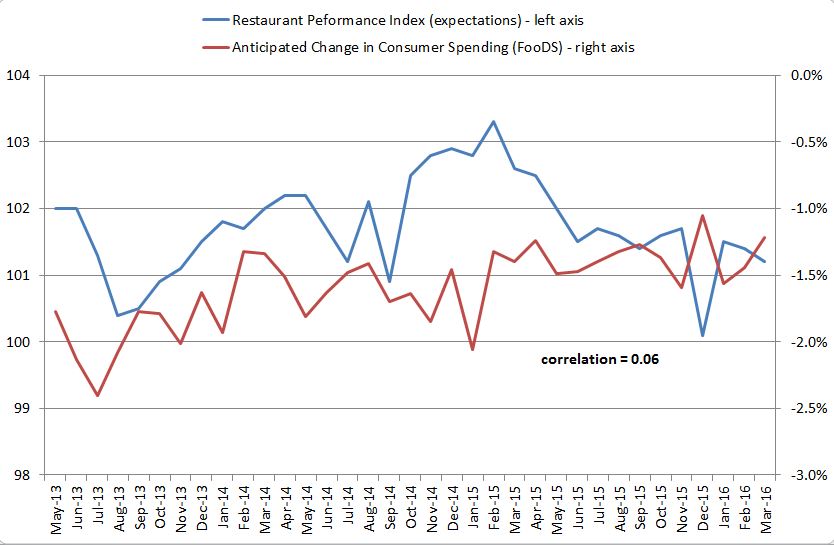

The results from the June 2016 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) are now in.

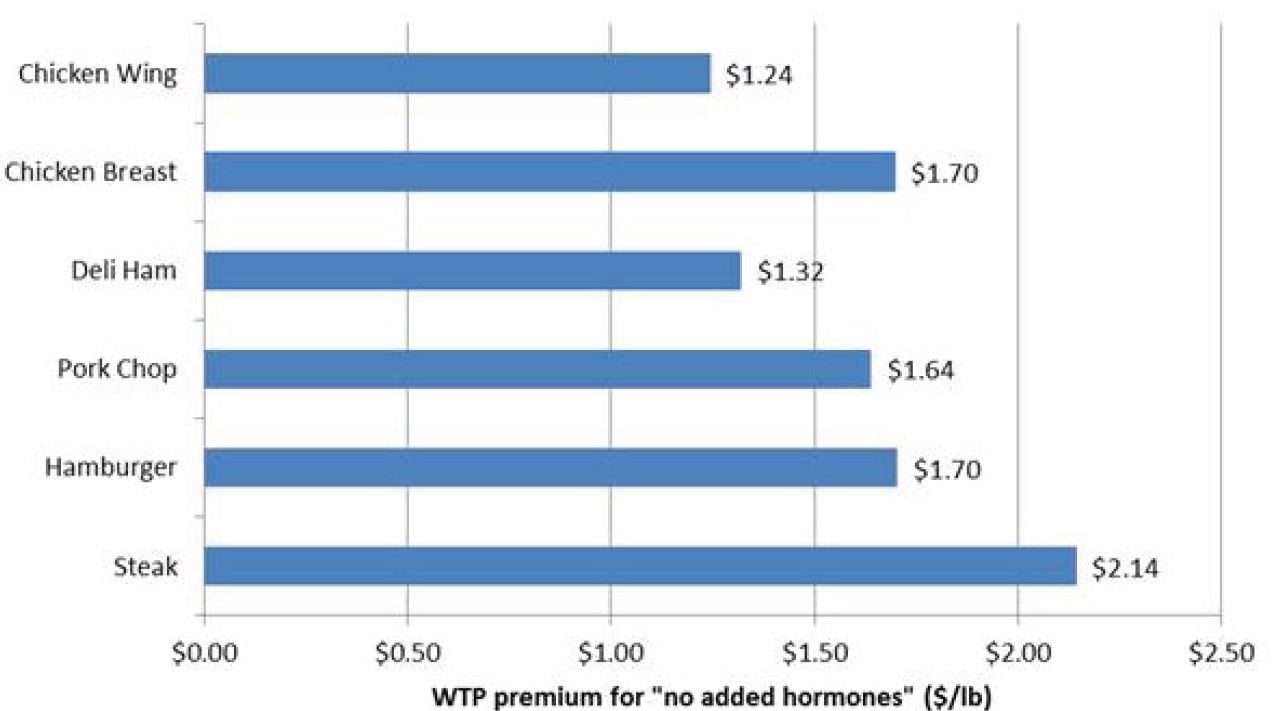

In terms of the monthly tracking portion of the survey, willingness-to-pay (WTP) decreased for all food products in June compared to May. This is the third month in a row that WTP has fallen for steak, chicken breast, and chicken wing, and the fourth month in a row that WTP has fallen for pork chops and deli ham.

There was a sizable increased in awareness of GMOs in the news this month, as was also the case for battery cages and beta-agonists. The largest percent increase in concern was for bird flu and farm animal welfare. The largest percent decrease in concern was for cancer and meat consumption, antibiotics, and E. coli.

Several new ad hoc questions were added this month.

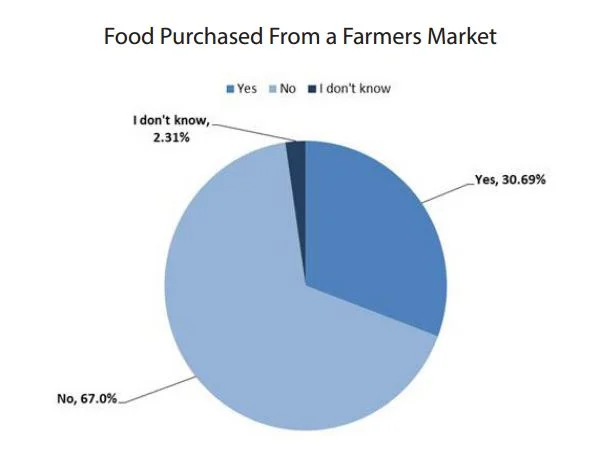

First, I followed up on some questions I'd previously asked in response to some research conducted by Marc Bellemare at University of Minnesota on food safety and farmers markets. In particular, participants were asked: “Have you or anyone in your household bought and eaten food from a farmers market in the past two weeks?”

Approximately 67% of participants stated they have not purchased food from a farmer’s market in the past two weeks. Less than one third of participants stated they have purchased food from a farmer’s market in the past two weeks. 2.31% of participants stated they did not know if they have purchased food from a farmer’s market in the past two weeks.

Here comes the interesting part. The people who shopped or ate at farmers markets were much more likely (20% vs. 2.5%) to say they had food poisoning in the past two weeks than people who did not eat or buy food at a farmers market. I'm surprised the difference is so large, but the results are perfectly in line with Marc's research.

There are other demographic differences as well. People who shopped or ate at farmers markets were more likely to be male (55.6% vs. 26%), to be on SNAP - aka food stamps - (24.1% vs. 14.5%), not be from the Midwest (90% vs. 80%), to have higher incomes ($91,167 vs.

$67,607), be younger (39 vs. 20 years of age), and be more liberal (3.4 vs. 2.9 on a 1 to 5 scale) on average than are people who did not shop at farmers markets.

Next, a couple questions were added on food waste. Participants were asked “Of all the food you buy at grocery stores and supermarkets, what percentage would you estimate is thrown away uneaten?”

About 80% of respondents said they throw away some portion of food that has been uneaten. Only about 20% said they threw away no food. About 60% of the sample said they throw away 10% of the food they buy or less. Only about 10% of respondents said they threw away 50% or more of the food they purchased. Across all respondents, the average percentage of food purchased that was eventually thrown away was estimated at about 17%.

Finally, there's been a lot of hand wringing on the possible effects of different sell-by, use-by, and expiration dates on food waste (e.g., witness this report from The Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

To explore this issue, respondents were randomly split into four groups and asked: “Supposed you found a package of food in your kitchen that had the following label <<label>>. What would you do?" Participants responded on a 5 point scale: 1 = I’d definitely eat it, 2 = I’d probably eat it, 3 = I’m not sure whether I’d eat it or throw it away, 4 = I’d probably throw it away, or 5 = I’d definitely throw it away.

Respondents randomly saw one of the following four labels:

- "Expiration Date June 9";

- “Sell by June 9”;

- “Best if Used by June 9”; or

- “Use by June 9”.

Note that the survey was purposefully fielded on June 10, one day after the date used in the question.

The most common answer across all categories was “I’d probably eat it”. The percent saying they’d definitely or probably eat the food was 60%, 73%, 68%, and 64% for the expiration date, sell by, best if used by, and use by labels. Less than 10% of respondents answered “I’d definitely throw it away” for all labels. The sell by label generated the least food waste, and it was the only label that generated less waste than the expiration date label. The differences in stated food waste was not particularly large for the four labels considered.