I was asked to make an appearance on Fox Business with Neil Cavuto this afternoon to talk about the impacts of the avian influenza (aka bird flu) outbreak on food prices. I had a couple other commitments that prevented me from going on air, but I'll share a few thoughts on the matter here via the lens of ECON 101.

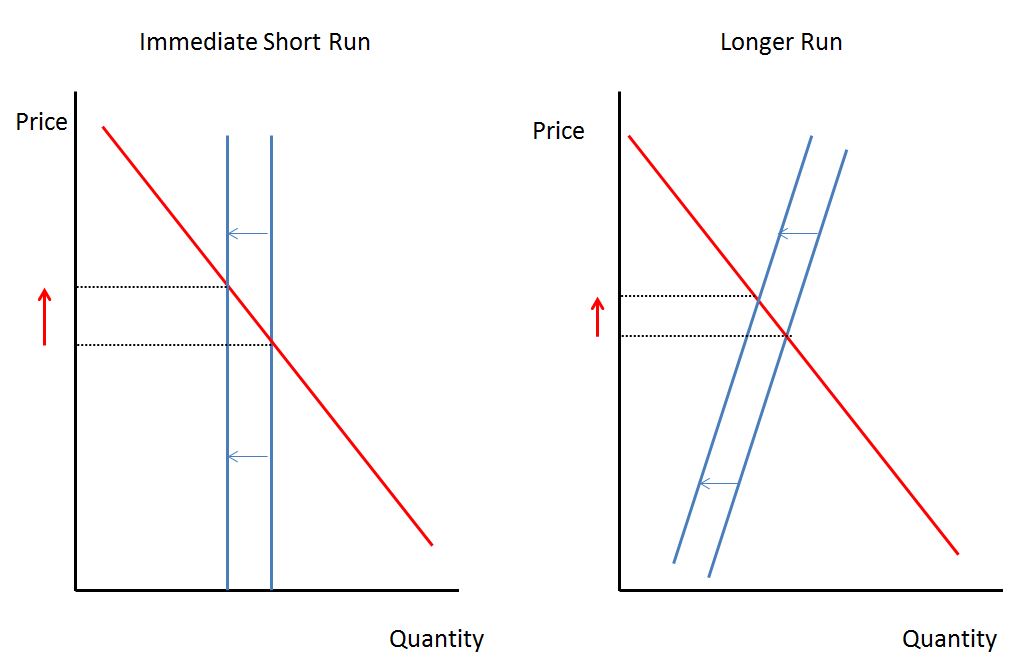

When a farm encounters a case of the bird flu, some birds die and others are euthanized. This reduces the supply of birds. In the graph below, this shifts the supply curve (the blue line) to the left. In the immediate short run, this translates into a direct reduction in the amount of turkey or eggs on the market as the supply curve is perfectly inelastic.

Consumers are now left to bargain over less quantity, and the shape of the demand curve (the red line) determines how high prices will rise. The more inelastic the demand curve (the less price responsive are consumers), the greater the price increase. In the longer run, the industry can adjust by adding new breeding stock, new houses, etc. (this makes the supply curve upward sloping rather than perfectly inelastic as shown in the right-hand graph), so the ultimate price effects will dampen over time.

This simple economic framework can be put to use to calculate possible impacts. According to data from USDA-APHIS, there have been around 3.3 million turkeys lost due to the flu. There are about 240 million turkeys in the nation. So, this represents a loss of about 1.4% of the turkey supply (this is the size of the supply shift in the quantity direction expressed in percentage terms). Assuming the elasticity of demand for turkey is about -0.5, this would imply that we could expect a (0.014/0.5)*100=2.8% price increase in the immediate short run. If the longer-run supply elasticity is, say, 0.8, the the longer-run price increase resulting from this supply reduction would be only (0.012/(0.5+0.8))*100=1.07%. What if the outbreak grows in size and doubles? Such that 6.6 million turkeys die? This would be a 2.8% reduction in supply which would cause a (0.028/0.5)*100=5.6% short-run increase in turkey prices.

Demand for eggs is likely much more inelastic because of fewer substitutes. The elasticity of demand for eggs is probably somewhere around -0.15 to -0.20. The USDA-APHIS data indicates that about 4 million chickens (I believe these are egg-laying chickens) have been killed due to the flu. There are about 300 million laying hens in the U.S., implying this is a supply reduction of about 1.3%. Following the same logic as before, a 1.3% supply shock in the short run would cause a (0.013/0.15)*100=8.7% increase in egg prices in the immediate short run. Why so much higher than for turkey? Because demand for eggs is likely more inelastic than is demand for turkey. If the outbreak in egg laying hens doubles, reducing supply by 2.6%, that would imply a price increase of 17.3% in the short run.

There are a couple reasons to suspect these effects may be overstated. First, exporters have slowed imports of chickens, turkey, and eggs because of the outbreak of the bird flu. That means domestically - within the U.S. - we'll have more supply on the market because not as much is going out of the country. Larger domestic supplies will mean downward pressure on domestic prices that push against the effects of the initial supply shock (although it should be noted that either way, world prices will rise). Second, the above analysis ignores substitutes. Higher turkey and egg prices will cause people to substitute toward beef and pork, which will have feedback effects on turkey and egg prices.