A recent article in Forbes ran under the headline “Regenerative Agriculture: The Next Trend In Food Retailing.” It appears regenerative is a trend that is taking a while to get going. Here is my comment on an article in the New York Times from almost exactly one year ago today.

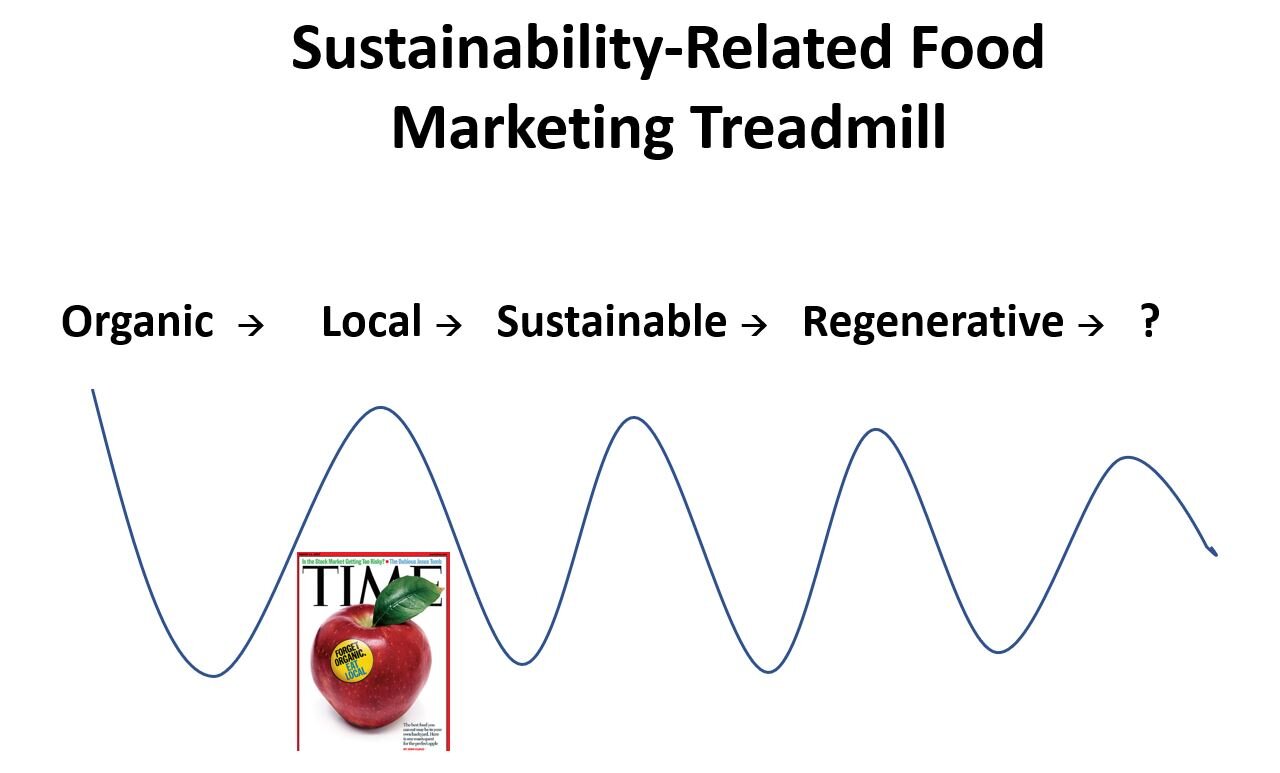

As shown in the figure below - taken from a presentation I gave about a month ago - Time Magazine had a cover image that said “Forget Organic. Eat Local” back on 2007. We subsequently seemed to move from local to sustainable. Now it’s regenerative. Next, it will be something else.

What causes the rise and fall, or rather the rise and plateau, of various food marketing claims?

None of these movements would have any traction if there wasn’t at least some underlying demand from consumers and investors for lowering the environmental impacts of food production, improving our health, giving farm animals a desirable life, or improving incomes of small farmers. That these base concerns exist provides the context for new movements to make their case for a place on dinner plates. Given that background context, upswings of food movements are driven the following factors.

Desire for authenticity and trustworthiness,

Myth making and seeking (“silver bullet” solutions that solve all the food system ills - environment, health, food security, and otherwise - seem particularly persuasive),

Romanticism of the small and natural,

Status-seeking (food as fashion), and

A core of committee devotees who are able to garner institutional support for the movement.

At some point, these movements lose their luster and become blasé. It’s not that the movement “dies” (e.g., organic food still appears to be experiencing strong sales growth), but rather the movements eventually lose their moral force and cultural cache. Why?

Here are a few thoughts.

As a movement grows, there is a need for standardization. What, exactly, is “local”? Food grown in your same state? Or region? Within 100 miles? Or 50 miles? What is “regenerative”? I still don’t know the answer to the last one. In the case of organic, competing definitions and conflicting standards ultimately led to U.S. federal standards and a certification program in 2002. While certification helps improve transparency and consumer communication, choices made in the process can alienate “true believers.” Consider, for example, the contentious issue of whether hydroponic crops can obtain an organic certification. Whatever decision the USDA made on that question (and countless others) was going to create winners and losers, with some people arguing that the movement has lost it’s way to gain mainstream appeal.

Corporatization and greenwashing. When these movements are small and growing and attracting consumers, the profits generated attract new entrants and competition, which eventually include “Big Food” and “Big Ag.” Large players can bring new knowledge, economies of scale, and open marketing channels, which helps bring down cost and helps the movement grow. However, many of these food movements are premised on the appeal to “natural” and “small,” and in many ways the movement ideology is often antithetical to scale. The very things that need to happen to mainstream a movement undermine credibility among a certain set of movement promoters.

Science evolves. When a movement is new and undefined, as “regenerative” is at the moment, it is easy to attach to it all of one’s hopes and dreams of food system reform. But, as the movement becomes more defined and standardized, scientists begin to conduct studies and find that the world is complex and nuanced. Studies find, for example, that organic food isn’t substantively more nutritious than conventionally produced food; and, that while organic uses fewer synthetic pesticides it also has lower yields and thus requires more land to produce the same amount of food. Studies find that localness of food has little relationship with greenhouse gas emissions. And so on. A movement loses some of its luster when it isn’t a silver bullet.

Mainstreaming removes prestige. When everyone can have organic food, it is no longer cool to eat organic food. Part of the appeal of high-end fashion, in both clothes and food, is exclusivity. The high price point helps these products maintain their position as status symbols, but as standardization, corporatization, competition, and scale economies come about, prices often fall. For some people, and for some goods, this can lead to a type of Veblen Good Effect, where demand falls as prices fall because the good loses its position as a status symbol.

It’s unlikely we’ll ever reach a point where there aren’t ebbs and flows in sustainability-related food trends, but there may be some ways to potentially partially step off the treadmill. One possibility is to move toward more outcome-oriented and objective (rather than process-focused, subjective) sustainability labels. That said, the advent of nutrition fact panels seems to have done little to stop the cycle of dietary-related fads and trends from low fat to low carb to high protein to gluten free to plant based. Maybe these ebbs and flows are just a part of human nature.