Blake Hurst, a farmer from Missouri, takes stock of the changes in cultural views toward food in the 10 years since the publication of Michael Pollan's highly influential, Omnivore's Dilemma.

Here's one bit that typifies some of the clash between the views of the food movement and those of a conventional farmer.

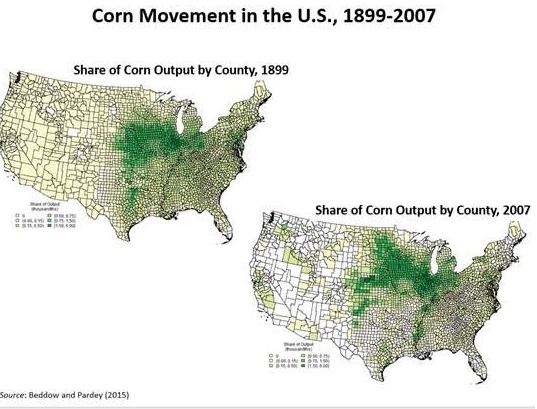

“Anybody who has followed the food movement over the last decade knows that corn is the serpent in the garden, the root of all evil, the original sin of industrialized agriculture. The writers and intellectuals who have changed the way we think about food and farming have seen the corn plant colonize, as they put it, an additional 25,000 square miles, an area almost the size of West Virginia. That’s got to hurt, if you like to eat artisanal kale in overpriced restaurants in Berkeley.

As a practical matter, agriculture has remained much the same because we farmers do what we do for good reasons. We use chemical fertilizers because people have to eat, and we can’t produce enough food without the help of commercial nitrogen fertilizer. We use chemical compounds to control weeds and insects because it’s the only way to do that without handing a hoe to millions of Americans every summer. We change corn into human food through animals (we eat the animals that eat the corn) and in food-processing factories that use corn products, because when it comes to changing changing sunshine to calories, corn is the most efficient plant known to man”

Hurst wraps up as follows:

“When it first hit the best-seller list in 2006, Pollan’s book was perfect for the times, laying out a series of challenges for the nation’s leading industry. He has changed how we think about food, increased scrutiny of those who provide that food, and spawned a growing and well-compensated cadre of chefs, documentary makers, food entrepreneurs, and other self-proclaimed food experts who are always ready with a quote or a Twitter hit about the dangers of modern food production. He hasn’t done much to change the way I farm, but he’s certainly changed the way farmers communicate with eaters.

Others will have to decide whether we’re better off for all of these changes. For farmers like me, the food movement has made life a little harder; it’s made me more conscious of how the decisions I make appear to others. I spend more time talking to people who are curious but uninformed about my industry. We now all talk like Pollan, but, a decade on, we still like a good hamburger or a perfectly prepared steak.”

There are a number of good points in the article. Read the whole thing here.