I was fortunate to spend the better part of 2011 on sabbatical in Paris working with the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Stephan Marette from INRA was a fantastic host.

Although I have returned many times since then to attend conferences and serve on an INRA advisory board, last week was the first time I revisited the city and our old neighborhood with my family. Here are a few reflections on the trip that relate to some of the themes on this blog.

1) We spent one morning on a food tour with a French chef. He took us to some familiar spots and some new ones too. In the course of conversation, I mentioned that I’d worked some with INRA, and I found his reaction interesting. For context, INRA is a bit like the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and a bit like the USDA National Institute for Food and Agricultural Research (NIFA), except rather than indirectly funding university professors through state agricultural experiment stations (as NIFA does in the US), INRA directly employs many PhD scientists who are housed at universities in addition to scientists at their own facilities. In any event, my guess is that if you mentioned ARS or NIFA to a chef in, say, New York, Chicago, or LA, they’d have no idea what you were talking about. ARS or NIFA who? But our French chef knew exactly who INRA was - and apparently he wasn’t much of a fan. He said that INRA only cares about producing more quantity and didn’t care about food quality, the later of which he argued was of greater importance to French consumers. I don’t think that characterization is exactly true (INRA does a lot of research on diets, health, food quality, and sustainability), but his perception of their objectives and purpose is nonetheless interesting and not entirely inaccurate. To the extent American consumers and taste-makers are familiar with US agricultural research agencies and universities, I wonder if they’d say the same? The research is clear that agricultural research produces significant benefits, but it is also true that future funding for agricultural research will depend, in part, on public support. That’s why we have to continue to find new ways to articulate the value of productivity enhancing research (for example, focusing on sustainability) and highlight the agricultural research that improves the both the price and the quality of food for consumers.

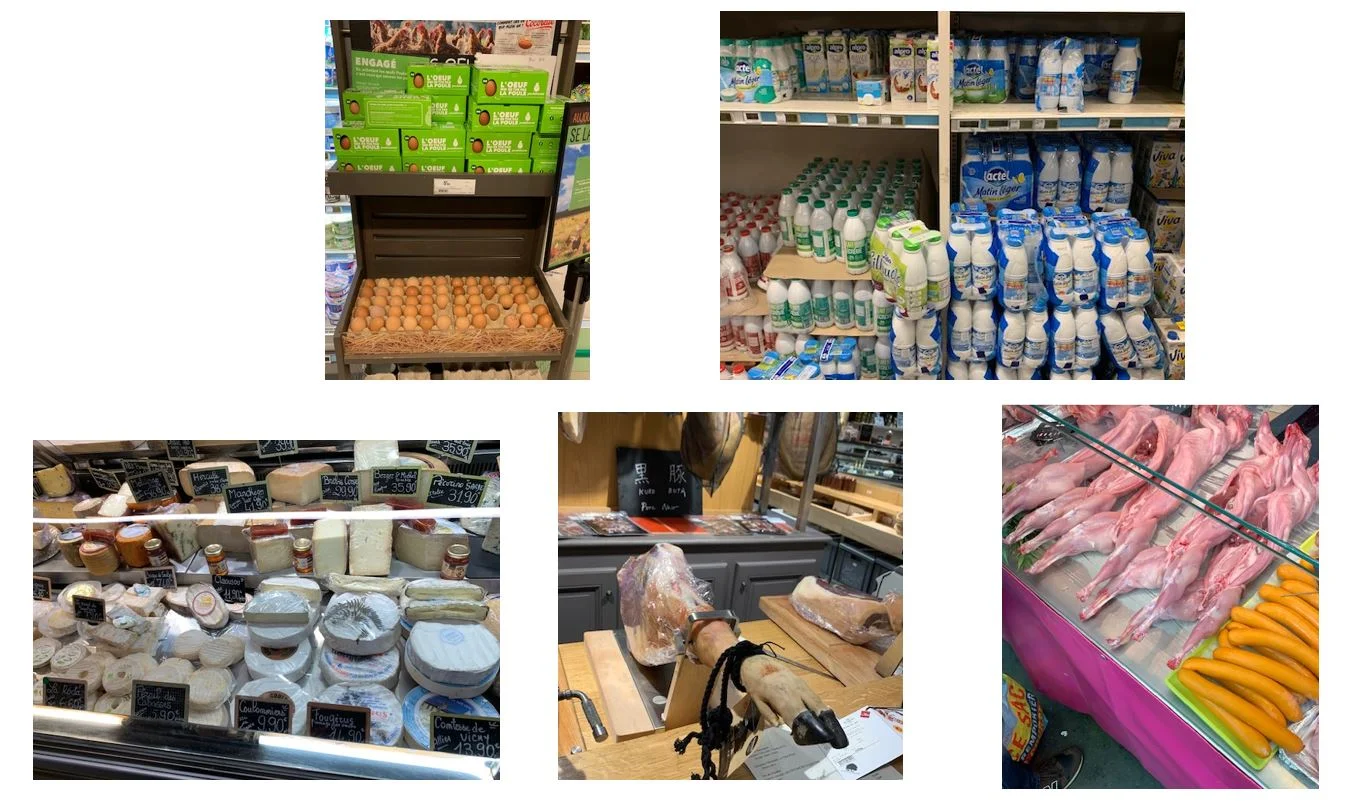

2) Given French consumer’s aversion to GMOs, attempts to ban glyphosate, and more, one might be tempted to argue that the French are more fearful of food safety risks. But, that can’t be exactly true. Below are a few pictures I snapped on the recent trip. These are not out of the ordinary in any way, but items one can find on the streets or usual supermarkets in Paris. What foods are available? Unrefrigerated eggs, unrefrigerated milk (it’s ultra high temperature pasteurized) sitting out next to the laundry detergent, cheeses from unpasteurized milk, hog legs (with hoof intact), raw rabbit carcasses for sell by street vendors, and much more. Many Americans I suspect would be very fearful of these common French foods. The French seem more accepting of “natural” food risks and less accepting of “modern/technological” food risks relative to Americans, although the example of the ultra-high pasteurized milks runs counter to that theme.

3. The French seem acutely interested in the origin/provenance of food and they often seem to use this attribute as a proxy for quality in the same way many Americans use brands. One of my current PhD students, Kendra Rash, is presenting some research at the upcoming meeting of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association. We are analyzing some data from an experiment conducted by Laurent Muller and Bernard Ruffieux with French consumers related to the value of different types of information. We found that information on origin is more highly valued than information on brand, price, organic, and more. I was a bit skeptical of this finding (mainly because other research I’ve done in the US shows origin to be a relatively unimportant food value), but my resent visit was reassuring and suggests our French findings are probably right. A good example is wine. In the US, we normally shop for wine by grape variety (Cabernet, Merlot, or Pinot Noir), but in France, wine is typically advertised by location and vineyard (and one is supposed to know which types of grapes are grown there).

4. Despite the differences, I’ll point to one of my favorite papers by by Pierre Dubois, Rachel Griffith, and Aviv Nevo that appeared in the American Economic Review. In many ways, their results suggest the food preferences of the French and Americans are not all that different; but our different economic systems alter the relative prices and food options available to us leading to different food choices. Here’s what I had to say about it when the paper first appeared about six years ago.

“I find these results interesting because there are many Americans who seems to subscribe to a view that the French have some kind of moral superiority when it comes to food and weight. I read these results to say that the French are, in large part, just responding to the economic incentives they face. And while they consume fewer calories than we do, it isn’t all that clear they’re better off given that they must pay more for many of the foods they desire than do Americans. ”