Many readers of this blog will probably remember the article by Danny Hakim (and the associated infographics) that ran in the New York Times back in October about the "broken promises" of GMOs. The article prompted some cheers and some legitimate criticisms.

After that article came out, one thing bugged me a bit. We have scores of experimental studies showing GMOs (particularly the Bt varieties) increase observed yield, so why don't we see a pronounced effect on aggregate, national yield trends? At about the same time these thoughts were swirling around in my head, I received a note from Jesse Tack at Kansas State University asking the same. As it turns out, we weren't the first to wonder about this. The most recent, 2016, National Academies report on GMOs noted the following:

“the nation-wide data on maize, cotton, or soybean in the United States do not show a significant signature of genetic-engineering technology on the rate of yield increase”

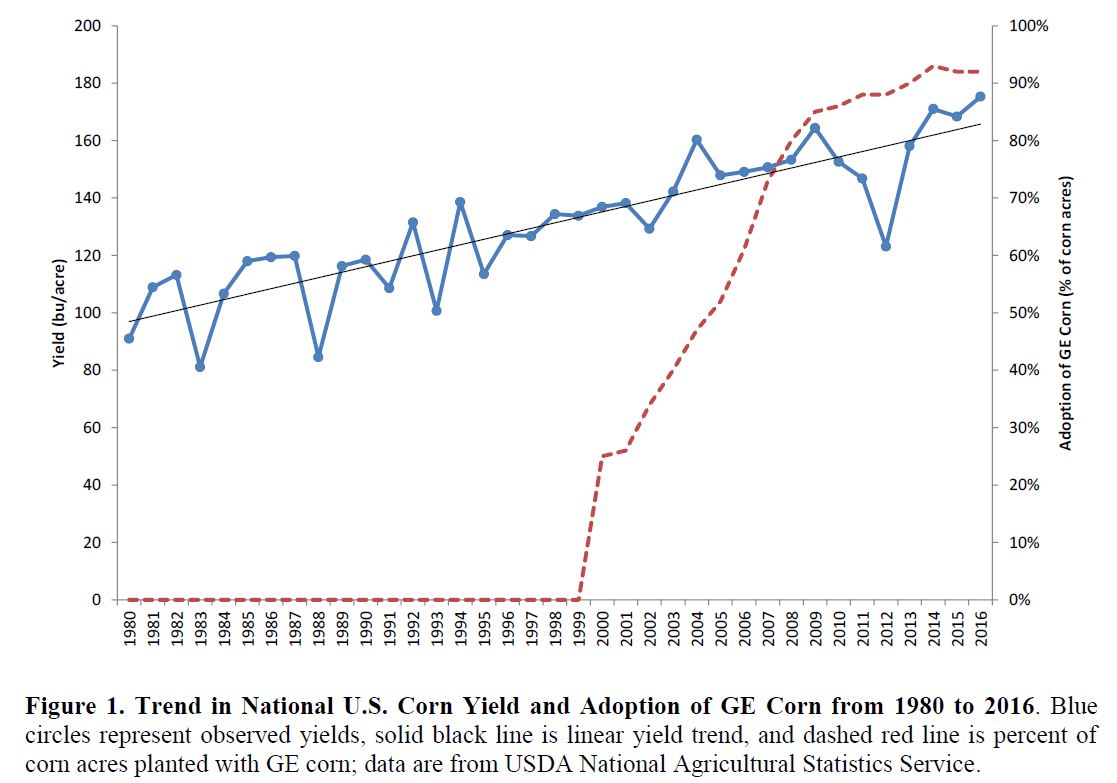

Here is a figure illustrating the phenomenon (from our paper I'll discuss more in a moment). Despite the massive increase in biotech adoption after 2000, national trend yields don't appear to have much changed.

So we began speculating about possible factors that could be driving this seeming discrepancy between the national, aggregate data on the one hand and the findings from experimental studies on the other, and wondered if aggregation bias might be an issue or whether the lack of controls for changes in weather and climate might be a factor. One of Jesse's colleagues, Nathan Hendricks, also suggested variation in soil characteristics, which when matched up with different timings of adoption in different areas, might also be an explanation.

To address these issues, Jesse, Nathan, and I wrote this working paper on the subject, which will be presented in May at conference put on by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Here are some of the key findings:

“In this paper, we show that simple analyses of national-level yield trends mask important geographic-, weather-, and soil-related factors that influence the estimated effect of GE crop adoption on yield. Coupling county-level data on corn yields from 1980 to 2015 and state-level adoption of GE traits with data on weather variation and soil characteristics, a number of important findings emerge. First, changes in weather and climatic conditions confound yield effects associated with GE adoption. Without controlling for weather variation, adoption of GE crops appears to have little impact on corn yields; however, once temperature and precipitation controls are added, GE adoption has significant effects on corn yields. Second, the adoption of GE corn has had differential effects on crop yields in different locations even among corn-belt states. However, we find that ad hoc political boundaries (i.e., states) do not provide a credible representation of differential GE effects. Rather, alternative measures based on soil characteristics provide a broad representation of differential effects and are consistent with the data. In particular, we find that the GE effect is much larger for soils with a larger water holding capacity, as well as non-sandy soils. Overall, we find that GE adoption has increased yields by approximately 18 bushels per acre on average, but this effect varies spatially across counties ranging from roughly 5 to 25 bushels per acre. Finally, we do not find evidence that adoption of GE corn led to lower yield variability nor do we find that current GE traits mitigate the effects of heat or water stress.”

To get a sense of the heterogeneity in yield effects, here is a graph of the estimated impacts of adoption of GMOs for counties that differ in terms of their soil's water holding capacity.

There's a lot more in the paper.