The results from the May 2017 edition of the Food Demand Survey (FooDS) are now in.

Some observations from the regular tracking portion of the survey:

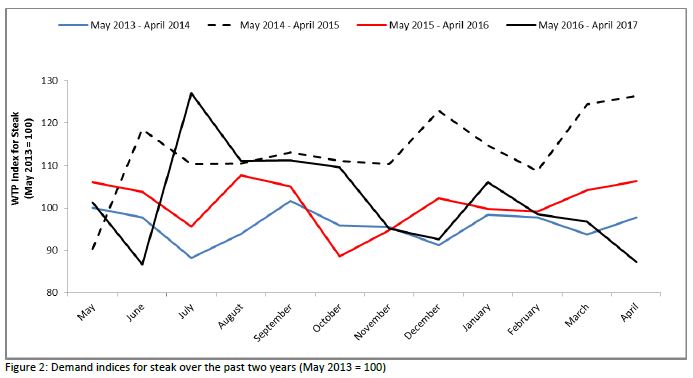

- Willingness-to-pay for the "premium" cuts from each meat species (steak, chicken breast, and pork chop) all increased this month compared to last; exactly the opposite was true for the the lesser-valued cuts (ground beef, wings, and deli ham). Willingness-to-pay for non-meat items declined significantly.

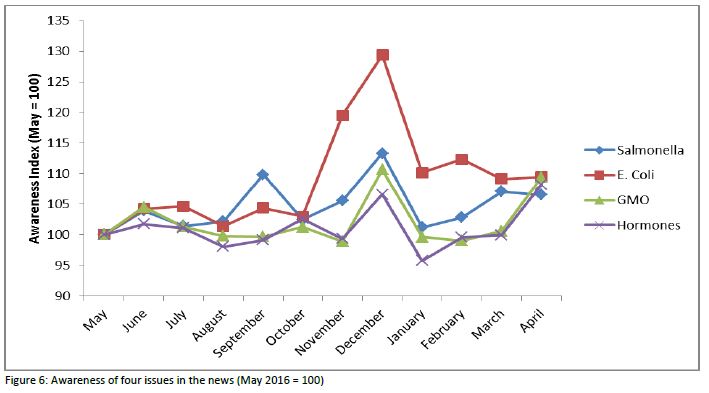

- Awareness and concern for a list of 17 items all fell this month compared to last. Concern for antibiotic use rose to the top three behind E Coli and Salmonella.

- Compared to last month, consumers increased expenditures on food at home but reduced expenditures on food away from home.

- Fewer people declared vegetarian status or indicated suffering from a food borne illness this month than has been the case for more than a year.

Several new ad hoc questions were added to the survey this month.

The first set of questions was added in response to some queries by Ranjith Ramanathan who is a meat scientist at Oklahoma State. He was interested in some issues related to how consumers buy and cook ground beef. To focus in on ground beef eaters, we first asked: “Do you eat ground beef patties (i.e., hamburgers)?” About 88% of the participants answered “yes”. Those who answered yes were then asked several questions related to cooking and buying ground beef patties.

Ground beef eaters were asked: “How do you determine the doneness of ground beef patties when cooking hamburger?” Choice options were: A) By using a meat thermometer, B) By visual observation (i.e., looking at the color of meat in the center of the patty), C) By cooking a certain length of time, or D) Other ways.

Approximately two-thirds of the participants who said they eat ground beef patties, stated they determine doneness by visual observation. Next most common, selected by about 18% of respondents, was determining doneness by length of cooking time. Only about 13.5% said they used a meat thermometer to determine doneness.

The next question asked: “What is your preference for the cooked internal color of ground beef patties?” Response options were: Red, Pink, Brown, or Another color.

The majority of participants, about 69%, stated they prefer the internal color of ground beef patties to be brown. About 26% of participants stated pink as their preferred cooked internal color. Only 5% of participants stated they would want a red center in their ground beef patties. Less than 1% stated they would want another color.

Participants were then asked: “To what internal temperature (degrees Fahrenheit) does the USDA recommend cooking ground beef patties?” Respondents could answer on a slider scale that ranged from 100 to 200 in one degree increments.

The average temperature stated by participants was 162 degrees Fahrenheit (the median was 161). The figure is remarkably close to the actual USDA recommendation of 160F. Nonetheless, a large share of participants were incorrect in their assessment. Thirty one percent stated a temperature less than 160 and 54.5% stated a temperature higher than 160. Even providing a five-degree margin of error, 28% stated a temperature less than 155 and 37% stated a temperature greater than 165. Thus, 28%+37%=65% of respondents gave an answer that was at least 5 degrees higher or lower than the USDA recommendation. Below is a histogram showing the distribution of responses.

Next, participants were asked: “How is the ground beef you normally buy packaged?” Response categories included text and photos of six different packaging options including: vacuum sealed, in a box as frozen patties, in butcher wrapped paper, as a chub, film wrapped, and in a tray.

Of those who eat ground beef, about one third stated they buy packaged ground beef in a tray. Ground beef in a film wrapped packaged was selected by about 28% of participants. About 18.7% of respondents stated they buy ground beef packaged as a chub. 8.5% said they normally buy ground beef in a box as frozen patties. Only 5.6% of participants said they normally purchase ground beef in a vacuum sealed package.

Finally, as I was grading final projects from one of my classes, I noticed one team, comprised of Ph.D. students Bernadette Chimai and Pedro Machado, asked an interesting question on a survey they'd posed to students. I modified it an included it on FooDs. Here is a screenshot of the question asked:

Participants most frequently stated that free range chickens were the most efficient (i.e., used the least amount of feed to produce a pound of meat) followed by grass fed cattle and grain fed chickens. However, response patterns were not necessarily symmetric. Thirty percent of participants believed feedlot cattle were least efficient (i.e., used the most feed to produce a pound of meat) followed by 25%, who indicated grass fed cattle as most inefficient. About an equal number of respondents thought free range pigs were both most and least efficient.

To help summarize the results, I calculated the difference in the percent of respondents who viewed an animal and production system as most efficient and subtracted it from the percent who viewed it as least efficient. Overall, free range and grain fed chickens were ranked highest in perceived efficienciency followed by free range pigs. Grain fed pigs and feedlot cattle were perceived as least efficient.